|

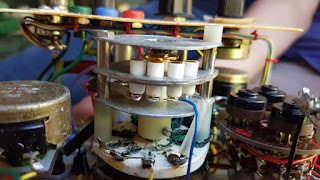

| Dad's prototype oxygen electrodes and commercially produced version on far right |

His expertise in the area of chemical processes became his key to many wonderful opportunities. Dad and mum had many trips to One Tree Island and Heron Island. They carried out research themselves and also had a series of research assistants who undertook research on a more continuous basis. This research (which dad referred to as recently as a 2014 edition of Reef Encounters in 2014, pp 30-31) became the basis of dad’s pioneering work into the metabolism and calcification rates of coral reefs, and gave an understanding of how fast coral reefs grow, and on which fronts.

While One Tree Island and Heron Island were where most of the research took place, dad visited many other sites. As a family, we went along for a few of these research trips as family finances allowed.

For Dad, it was during the Second International Symposium on Coral Reefs in 1973 on board the Marco Polo (Link to proceedings) that new horizons opened for him. He met, and held his own, with international experts in coral reef research. He made many contacts, who later became friends and colleagues who encouraged him to move into marine science as a career instead of a hobby.

Heron Island

| |

| Aerial view of Heron over to Wistari Reef |

In 1970, dad took his long service leave to do more research and we lived on Heron Island for over 3 months from August to October. Heron then was quite different to how it is now. There was a research station and a resort. The resort, however, was very laid back and relaxed with little to no structured activities for the guests. They had one shop which had a timber window which was lifted open to form a servery once a day for a few hours selling essentials, lollies and ice cream. If we were lucky they had passionfruit icecream, but that was a real luxury. There was generally very little interaction between the resort and the research station.

|

| Dad's field equipment which he designed and built |

|

| Dad with Peter Davies with whom he collaborated on many projects |

|

| The gold electrodes on Dad's pH meter, the first in the world with 3 decimal point accuracy |

|

| Dad's field equipment that he designed and built |

|

| Dad's field equipment on a research boat on Heron |

Cate: The Heron Island Research Station comprised a series of labs, dormitory accommodation and 3 houses. The houses were open plan 2 bedroom with a bathroom and walk through kitchen providing the separation between the bedrooms. Anne and Bill lived in the house with mum and dad. I lived in the dorms with our babysitter. Mum and dad had engaged Debbie to come with us to Heron so that mum and dad could go out and do their research and we would have someone to look after us. Poor Debbie got so sick of us calling out “Debbie?”, “Debbie!”, “Debbie?”. One day she had had enough and said to stop calling out Debbie!! So, from then on, we called her Fred. We all did, mum and dad included.

Heron was magical. For us kids it was our first time on the reef. I was 8, Bill was 5 and Anne was 3. We had so much freedom and loved every minute of it. One day, Dad was packing and babysitting 3-year old Anne while Mum was taking photographs. Mum came back and asked where Anne was. We looked everywhere, she was nowhere to be seen. Finally dad saw her in the binoculars out near the edge of the reef.

Tides on Heron are big; eight feet from high to low. When the tide is low, you can walk all the way to the edge in very shallow water. But when it comes in, it comes in fast and covers the reef flat very quickly. Dad raced out to Anne who was wandering around at her usual “blissful” pace and Dad, after grabbing Anne and giving her a hug, got upset and said “What were you doing out there? Don;t you know the tide is coming in?” Her reply, “I know. That’s why I was coming back”. If dad hadn’t seen her out there, she would have drowned.

Dad took us out fishing. We would usually go to the lagoon and fish (allowable in those days) with hand lines. The water was so clear that you could almost pick which fish’s mouth to drop the bait into. Sometimes we caught sharks, and invariably it was Anne who caught them. We would hear this little squeak and turn to see the line running through her hands and her sliding to the side of the boat. She would say calmly “I think I caught a shark”. We would usually fill a plastic garbage bin fairly quickly, then come back and dad would clean and fillet the fish and freeze it for later.

Heron was magical. For us kids it was our first time on the reef. I was 8, Bill was 5 and Anne was 3. We had so much freedom and loved every minute of it. One day, Dad was packing and babysitting 3-year old Anne while Mum was taking photographs. Mum came back and asked where Anne was. We looked everywhere, she was nowhere to be seen. Finally dad saw her in the binoculars out near the edge of the reef.

Tides on Heron are big; eight feet from high to low. When the tide is low, you can walk all the way to the edge in very shallow water. But when it comes in, it comes in fast and covers the reef flat very quickly. Dad raced out to Anne who was wandering around at her usual “blissful” pace and Dad, after grabbing Anne and giving her a hug, got upset and said “What were you doing out there? Don;t you know the tide is coming in?” Her reply, “I know. That’s why I was coming back”. If dad hadn’t seen her out there, she would have drowned.

Dad took us out fishing. We would usually go to the lagoon and fish (allowable in those days) with hand lines. The water was so clear that you could almost pick which fish’s mouth to drop the bait into. Sometimes we caught sharks, and invariably it was Anne who caught them. We would hear this little squeak and turn to see the line running through her hands and her sliding to the side of the boat. She would say calmly “I think I caught a shark”. We would usually fill a plastic garbage bin fairly quickly, then come back and dad would clean and fillet the fish and freeze it for later.

|

| The Beach rocks from which many dinners were caught |

Occasionally, I would be allowed to go out when dad was researching at night. He needed to track how far and how fast the water was moving. This is no mean feat in daylight, but at night it became even more difficult. He used fluorescein dye and a small float with a light. The float did not move at exactly the same pace as the water but it gave a good indication of where to look for the fluorescein. The dye is bright yellow green and quite easy to spot. These nights out on the reef were magic. Sometimes we would encounter flying fish. Sometimes there would be natural fluorescence in the water and everywhere the boat moved, the water would sparkle.

Food on Heron was only delivered by boat and certainly not daily or even weekly. Fresh bread and milk were luxuries. We mostly had powdered milk and I remember it being warm. Yuk. Power on the island was (and still is) supplied by generator. Fish was our staple protein source.

One day the King Fish were running close to the beachrock. I remember Dad going and getting a line. He was running and yelling with joy. King Fish are fun to catch. Very playful. And catching them amongst the coral bommies without the line getting cut was an art. Dad hooked one and it gave him a long battle. Dad was over the moon when he finally landed his fish. For us, it was fun to watch. A battle of brain versus instinct.

One Tree Island

Mum and Dad had done much research on One Tree since the mid 1960's. In 1972 the whole family went to One Tree Island for 2 weeks. One Tree is even more remote than Heron. To get there, you have to travel to Heron on the Shuttle boat, then hope the weather is good so that you can go to One Tree in a skiff. The weather and the tide have to be perfect so that the boat can get through the very small break in the fringing reef and get into the lagoon on One Tree. |

| Earlier trip to One Tree Mum and Dad doing research |

|

| Mum and the make-shift chemistry lab on an early trip to One Tree |

|

| One Tree Island Research Station |

|

| Inside the research station |

|

| recent photo of One Tree Island Research Station |

|

| Recent photo of One Tree lagoon |

The beaches on Heron are very fine coraline sand. One Tree is different.The beaches, and the whole island are made of very coarse coral rubble. You cannot walk anywhere without shoes on. Accommodation was in tents. It was a very primitive set up compared to Heron.

|

| The "beach" on One Tree - all coral rubble |

This time we were 10, 7 and 5 respectively. Snorkelling and fishing were daily pastimes.

|

| The kids on One Tree |

This was Dads favourite place. He loved One Tree Island. Even with all the wonderful places he went before and after, One Tree always held a special place in his heart.

|

| One Tree lagoon |

One day we kids were swimming in the shallow bay in front of the research station. A big fish joined us. We yelled out to mum and dad about the big fish. They came running down thinking it was probably a shark. It was a huge cod. About 4 feet long, swimming around us. Just inquisitive.

Cate: "Sometimes I would be sent down to “catch dinner”. I would take one line, one bait and bring back one fish. Every time. It was usually a Spangled Emperor or Sweet Lip, sometimes a Coral Trout. Sometimes the fish were so big I had to drag them back to the house. We were spoilt. The fishing was so easy. Fishing anywhere else after that always seemed like hard work."

We would sometimes join Dad when he went out to do research. He would always make sure that there would be time to do his work, but also enough time to also have a snorkel or go exploring somewhere. One spot he took us snorkelling was like a deep cleft. The opening was quite narrow and coral adorned the walls as far down as the light penetrated. It was one of those magic places that you never forget. There were sharks down in the deeper water below us, but they were not in any way threatening.

There was no toilet on One Tree. Everyone relieved themselves on the Point. The Point was a spit of land and there was a gutter in the reef. The tide came in the gutter and on the falling tide washed everything out to sea. The system that was used to provide privacy was a washed-up buoy which was placed on a stake if the Point was in use. Some of the best coral reef could be found in the gutter, but we rarely swam there :-).

One of dad’s longtime research assistants Katarina Lundgren (now Moberg) has very fond memories of her time on One Tree She reconnected with Dad and mum a few years ago and they have kept in regular contact since. She wrote a short story about what it was like living and working on One Tree.

Cate: "Sometimes I would be sent down to “catch dinner”. I would take one line, one bait and bring back one fish. Every time. It was usually a Spangled Emperor or Sweet Lip, sometimes a Coral Trout. Sometimes the fish were so big I had to drag them back to the house. We were spoilt. The fishing was so easy. Fishing anywhere else after that always seemed like hard work."

We would sometimes join Dad when he went out to do research. He would always make sure that there would be time to do his work, but also enough time to also have a snorkel or go exploring somewhere. One spot he took us snorkelling was like a deep cleft. The opening was quite narrow and coral adorned the walls as far down as the light penetrated. It was one of those magic places that you never forget. There were sharks down in the deeper water below us, but they were not in any way threatening.

There was no toilet on One Tree. Everyone relieved themselves on the Point. The Point was a spit of land and there was a gutter in the reef. The tide came in the gutter and on the falling tide washed everything out to sea. The system that was used to provide privacy was a washed-up buoy which was placed on a stake if the Point was in use. Some of the best coral reef could be found in the gutter, but we rarely swam there :-).

One of dad’s longtime research assistants Katarina Lundgren (now Moberg) has very fond memories of her time on One Tree She reconnected with Dad and mum a few years ago and they have kept in regular contact since. She wrote a short story about what it was like living and working on One Tree.

Lizard Island

In December 1974 the family spent 2 weeks on Lizard Island. This island is totally different to both Heron and One Tree. Heron and One Tree are coral atolls and sit just above sea level. Lizard is a rocky part of the mainland became separated by the ocean. It has mountains and valleys and rises significantly above sea level. We flew there by plane. At that time the only service available to Lizard was provided by Bush Pilots. Lizard is at the end of the mail run. This was an eye opener for us. We would stop in locations to deliver a few letters or a loaf of fresh bread. I clearly remember landing on a property on Cape Flattery that had a brick runway (Mum tells me it was a brick on the runway - childhood memories :-)).

The landing strip on Lizard is compacted sand and has a lot of grade from one end to the other and a steep drop-off to the ocean at either end. It is quite an experience landing and taking off there.

The landing strip on Lizard is compacted sand and has a lot of grade from one end to the other and a steep drop-off to the ocean at either end. It is quite an experience landing and taking off there.

|

| South and Palfrey Islands adjoining Lizard Island |

On Lizard we stayed in tents again, but these were much grander than those on One Tree. Our tents were a long way back from the beach and we remember running across the scalding sand barefoot and sinking into the water in relief. Of course we had to get back again too. Eventually we moved the tent closer to the beach to avoid the hot track and also to get away from the green ants which took up residence.

Dad took us on many wonderful trips while we were there. The lagoon has two other islands that form part of the periphery; South Island and Palfrey Island. There are also other beaches on Lizard that are only accessible by boat. On one of these we found coconuts. The first I had seen in the wild. It also had drifts of pumice that had washed ashore from some underwater volcano. I don’t remember how deep the drift was, but it was certainly memorable. We tried to bury ourselves in it. It was an amazing beach and so different to the rest of Lizard Island.

Now that we were older and more proficient snorkellers we'd all jump into the deep water off the side of the boat when we joined dad for research outings. Anne had a legendary ability to fail to see sharks (or see herself as a potential food source). So, while still only 7, she would often head to the edge of the reef to look at the "big fish" (gropers), much to mum's horror. Dad was often blissful unaware of the situation as he was absorbed in his work and would not help the situation when he'd come back to the boat and asked "Did you see the shark?"

When we left Lizard it was again on a Bush Pilots plane. We am not sure of the model but it held probably 8-10 passengers and had two propellers, one on each wing. We taxied to the end of the runway and turned to take off, but one of the wheels got bogged in the sand. We all had to get out of the plane. That was not enough for the plane to get free, so the pilot got dad and the other men on the plane to stand under the wing and push up while he gunned the props. Certainly not something that would even be considered today. But it worked.

Chasing a dream

At 40 Dad decided that the food industry was not where he wanted to be for the rest of his life. He followed his passion and moved into Marine Science. He was making his hobby his life journey. The first step was to formalise his qualifications with a PhD - and there was no other place better to do this than Hawaii. It takes real courage, commitment and hard work to chase a dream. It is not the romantic notion that people envisage it might be. It involved letting go of a much-loved house, boat and lifestyle and leaving behind many dear friends. But the rewards at the end seemed worth it. For Dad and Mum to walk away from stable careers and an established household to chase their dream, moving to another country with financial uncertainty and an unknown future was a huge leap of faith.

Next Page 1976-1978 Hawaii Dad's PhD

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments on this site will be moderated.